-

Imperious Sinner barrels into Australian Open round three

Imperious Sinner barrels into Australian Open round three

-

Storms, heavy rain kill 9 children across Afghanistan

-

Games giant Ubisoft suffers share price collapse

Games giant Ubisoft suffers share price collapse

-

Exhausted Wawrinka battles on in Melbourne farewell after five-set epic

-

'Too dangerous to go to hospital': a glimpse into Iran's protest crackdown

'Too dangerous to go to hospital': a glimpse into Iran's protest crackdown

-

Bruised European allies wary after Trump's Greenland climbdown

-

Austrian ex-agent goes on trial in Russia spying case

Austrian ex-agent goes on trial in Russia spying case

-

Japan suspends restart of world's biggest nuclear plant

-

Djokovic, Swiatek roll into Melbourne third round, Keys defence alive

Djokovic, Swiatek roll into Melbourne third round, Keys defence alive

-

New Zealand landslips kill at least two, others missing

-

Djokovic says heaving Australian Open crowds 'good problem'

Djokovic says heaving Australian Open crowds 'good problem'

-

Swiatek in cruise control to make Australian Open third round

-

Austrian ex-agent to go on trial in Russia spying case

Austrian ex-agent to go on trial in Russia spying case

-

Bangladesh launches campaigns for first post-Hasina elections

-

Afghan resistance museum gets revamp under Taliban rule

Afghan resistance museum gets revamp under Taliban rule

-

Multiple people missing in New Zealand landslips

-

Sundance Film Festival hits Utah, one last time

Sundance Film Festival hits Utah, one last time

-

Philippines convicts journalist on terror charge called 'absurd'

-

Anisimova grinds down Siniakova in 'crazy' Australian Open clash

Anisimova grinds down Siniakova in 'crazy' Australian Open clash

-

Djokovic rolls into Melbourne third round, Keys defence alive

-

Vine, Narvaez take control after dominant Tour Down Under stage win

Vine, Narvaez take control after dominant Tour Down Under stage win

-

Chile police arrest suspect over deadly wildfires

-

Djokovic eases into Melbourne third round - with help from a tree

Djokovic eases into Melbourne third round - with help from a tree

-

Keys draws on champion mindset to make Australian Open third round

-

Knicks halt losing streak with record 120-66 thrashing of Nets

Knicks halt losing streak with record 120-66 thrashing of Nets

-

Philippine President Marcos hit with impeachment complaint

-

Trump to unveil 'Board of Peace' at Davos after Greenland backtrack

Trump to unveil 'Board of Peace' at Davos after Greenland backtrack

-

Bitter-sweet as Pegula crushes doubles partner at Australian Open

-

Hong Kong starts security trial of Tiananmen vigil organisers

Hong Kong starts security trial of Tiananmen vigil organisers

-

Keys into Melbourne third round with Sinner, Djokovic primed

-

Bangladesh launches campaigns for first post-Hasina polls

Bangladesh launches campaigns for first post-Hasina polls

-

Stocks track Wall St rally as Trump cools tariff threats in Davos

-

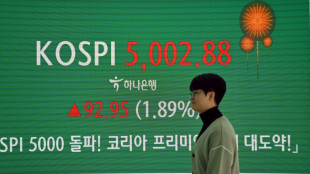

South Korea's economy grew just 1% in 2025, lowest in five years

South Korea's economy grew just 1% in 2025, lowest in five years

-

Snowboard champ Hirano suffers fractures ahead of Olympics

-

'They poisoned us': grappling with deadly impact of nuclear testing

'They poisoned us': grappling with deadly impact of nuclear testing

-

Keys blows hot and cold before making Australian Open third round

-

Philippine journalist found guilty of terror financing

Philippine journalist found guilty of terror financing

-

Greenlanders doubtful over Trump resolution

-

Real Madrid top football rich list as Liverpool surge

Real Madrid top football rich list as Liverpool surge

-

'One Battle After Another,' 'Sinners' tipped to top Oscar noms

-

Higher heating costs add to US affordability crunch

Higher heating costs add to US affordability crunch

-

Eight stadiums to host 2027 Rugby World Cup matches in Australia

-

Plastics everywhere, and the myth that made it possible

Plastics everywhere, and the myth that made it possible

-

Interim Venezuela leader to visit US

-

Australia holds day of mourning for Bondi Beach shooting victims

Australia holds day of mourning for Bondi Beach shooting victims

-

Liverpool cruise as Bayern reach Champions League last 16

-

Fermin Lopez brace leads Barca to win at Slavia Prague

Fermin Lopez brace leads Barca to win at Slavia Prague

-

Newcastle pounce on PSV errors to boost Champions League last-16 bid

-

Fermin Lopez brace hands Barca win at Slavia Prague

Fermin Lopez brace hands Barca win at Slavia Prague

-

Kane double fires Bayern into Champions League last 16

No brain, no problem: Tiny jellyfish can learn from experience

Caribbean box jellyfish are barely a centimetre long and have no brain.

But these gelatinous, fingernail-sized creatures are capable of learning from visual cues to avoid swimming into obstacles -- a cognitive ability never before seen in animals with such a primitive nervous system, researchers said on Friday.

Their performance of what is called "associative learning" is comparable to far more advanced animals such as fruit flies or mice, which have the notable benefit of having a brain, the researchers said.

The Caribbean box jellyfish, or Tripedalia cystophora, is known to be able to navigate through murky water and a maze of submerged mangrove roots.

These scenarios throw up plenty of dangers that could damage the jellyfish's fragile gelatinous membrane which envelops its bell-shaped body.

But they avoid harm thanks to four visual sensory centres called rhopalia, each of which has lens-shaped eyes and around a thousand neurons.

For comparison, fruit flies are packing 200,000 neurons in their tiny brains.

Cnidarians -- the animal group which includes jellyfish, sea anemones and coral -- are brainless, instead getting by with a "dispersed" central nervous system.

Despite this considerable disadvantage, the Caribbean box jellyfish responds to what is called "operant conditioning," according to the study in the journal Current Biology.

This means they can be trained to "predict a future problem and try to avoid it," said Anders Garm, a marine biologist at the University of Copenhagen and the study's lead author.

Garm told AFP that this capacity is "more complex than classical conditioning," which is best known for Russian neurologist Ivan Pavlov's experiments showing that dogs cannot help but salivate when they see their food bowl.

- 'Very intriguing' -

To test the jellyfish, the researchers put them in a small, water-filled tank with stripes of varying darkness on the glass walls to represent mangrove roots.

After a few bumps into the walls, the jellyfish quickly learned to move through the parts of the enclosures where the bars were least visible.

If the bars were made more prominent, the jellyfish never hit the walls, remaining safely in the centre of the tank. However this was not ideal for scrounging around for food.

If the stripes were removed entirely, the jellyfish constantly ran into the walls of the tank.

"If you separate the two stimuli, there is no learning," Garm concluded.

The jellyfish learned their lesson in between three to six tries, "which is basically the same amount of trials for what we would normally consider an advanced animal, like a fruit fly, a crab or even a mouse," he said.

They said their research supports the theory that even animals with a very small number of neurons are capable of learning.

That such a simple organism is able to achieve this feat "points to the very intriguing fact that this may be a fundamental property of nerve systems," Garm said.

Cnidarians are a "sister group" to the animal group that includes most other animals -- including humans.

Garm suggested that some 500 million years ago, a common ancestor of the two groups could have developed a nervous system that was already able to learn by association.

M.Schneider--VB