-

'Extremely lucky' Djokovic into Melbourne semi-finals as Musetti retires

'Extremely lucky' Djokovic into Melbourne semi-finals as Musetti retires

-

'Animals in a zoo': Players back Gauff call for more privacy

-

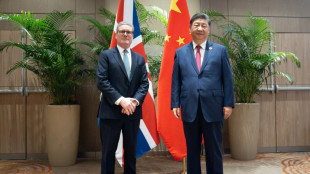

Starmer heads to China to defend 'pragmatic' partnership

Starmer heads to China to defend 'pragmatic' partnership

-

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

-

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

-

South Korea's ex-first lady jailed for 20 months for taking bribes

-

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

-

South Korea's ex-first lady jailed for 20 months for corruption

South Korea's ex-first lady jailed for 20 months for corruption

-

Minnesota congresswoman unbowed after attacked with liquid

-

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

Backlash as Australia kills dingoes after backpacker death

-

Brazil declares acai a national fruit to ward off 'biopiracy'

-

Anisimova 'loses her mind' after Melbourne quarter-final exit

Anisimova 'loses her mind' after Melbourne quarter-final exit

-

Home hope Goggia on medal mission at Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics

-

Omar attacked in Minneapolis after Trump vows to 'de-escalate'

Omar attacked in Minneapolis after Trump vows to 'de-escalate'

-

Pistons escape Nuggets rally, Thunder roll Pelicans

-

Dominant Pegula sets up Australian Open semi-final against Rybakina

Dominant Pegula sets up Australian Open semi-final against Rybakina

-

'Animals in a zoo': Swiatek backs Gauff call for more privacy

-

Japan PM's tax giveaway roils markets and worries voters

Japan PM's tax giveaway roils markets and worries voters

-

Amid Ukraine war fallout, fearful Chechen women seek escape route

-

Rybakina surges into Melbourne semis as Djokovic takes centre stage

Rybakina surges into Melbourne semis as Djokovic takes centre stage

-

Dollar struggles to recover from losses after Trump comments

-

Greenland blues to Delhi red carpet: EU finds solace in India

Greenland blues to Delhi red carpet: EU finds solace in India

-

Will the EU ban social media for children in 2026?

-

Netherlands faces 'test case' climate verdict over Caribbean island

Netherlands faces 'test case' climate verdict over Caribbean island

-

Rybakina stuns Swiatek to reach Australian Open semi-finals

-

US ouster of Maduro nightmare scenario for Kim: N. Korean ex-diplomat

US ouster of Maduro nightmare scenario for Kim: N. Korean ex-diplomat

-

Svitolina credits mental health break for reaching Melbourne semis

-

Japan's Olympic ice icons inspire new skating generation

Japan's Olympic ice icons inspire new skating generation

-

Safe nowhere: massacre at Mexico football field sows despair

-

North Korea to soon unveil 'next-stage' nuclear plans, Kim says

North Korea to soon unveil 'next-stage' nuclear plans, Kim says

-

French ex-senator found guilty of drugging lawmaker

-

US Fed set to pause rate cuts as it defies Trump pressure

US Fed set to pause rate cuts as it defies Trump pressure

-

Sleeping with one eye open: Venezuelans reel from US strikes

-

Venezuela's acting president says US unfreezing sanctioned funds

Venezuela's acting president says US unfreezing sanctioned funds

-

KPop Demon Hunters star to open Women's Asian Cup

-

Trump warns of 'bad things' if Republicans lose midterms

Trump warns of 'bad things' if Republicans lose midterms

-

Russian strikes in Ukraine kill 12, target passenger train

-

With Maduro gone, Venezuelan opposition figure gets back to work

With Maduro gone, Venezuelan opposition figure gets back to work

-

Celebrities call for action against US immigration raids

-

Rubio to warn Venezuela leader of Maduro's fate if defiant

Rubio to warn Venezuela leader of Maduro's fate if defiant

-

Denver QB Nix 'predisposed' to ankle injury says coach

-

Lula, Macron push for stronger UN to face Trump 'Board of Peace'

Lula, Macron push for stronger UN to face Trump 'Board of Peace'

-

Prass stunner helps Hoffenheim go third, Leipzig held at Pauli

-

Swiss Meillard wins final giant slalom before Olympics

Swiss Meillard wins final giant slalom before Olympics

-

CERN chief upbeat on funding for new particle collider

-

Trump warns US to end support for Iraq if Maliki returns

Trump warns US to end support for Iraq if Maliki returns

-

Judge reopens sexual assault case against goth rocker Marilyn Manson

-

South Korea's ex-first lady to learn verdict in corruption case

South Korea's ex-first lady to learn verdict in corruption case

-

Rosenior dismisses Chelsea exit for 'untouchable' Palmer

Ostrich and emu ancestor could fly, scientists discover

How did the ostrich cross the ocean?

It may sound like a joke, but scientists have long been puzzled by how the family of birds that includes African ostriches, Australian emus and cassowaries, New Zealand kiwis and South American rheas spread across the world -- given that none of them can fly.

However, a study published Wednesday may have found the answer to this mystery: the family's oldest-known ancestors were able to take wing.

The only currently living member of this bird family -- which is called palaeognaths -- capable of flight is the tinamous in Central and South America. But even then, the shy birds can only fly over short distances when they need to escape danger or clear obstacles.

Given this ineptitude in the air, scientists have struggled to explain how palaeognaths became so far-flung.

Some assumed that the birds' ancestors were split up when the supercontinent Gondwana started breaking up 160 million years ago, creating South America, Africa, Australia, India, New Zealand and Antarctica.

However, genetic research has shown that "the evolutionary splits between palaeognath species happened long after the continents had already separated," lead study author Klara Widrig of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History told AFP.

- Wing and a prayer -

Widrig and colleagues analysed the specimen of a lithornithid, the oldest palaeognath group for which fossils have been discovered. They lived during the Paleogene period 66-23 million years ago.

The fossil of the bird Lithornis promiscuus was first found in the US state of Wyoming, but had been sitting in the Smithsonian museum's collection.

"Because bird bones tend to be delicate, they are often crushed during the process of fossilisation, but this one was not," she said.

"Crucially for this study, it retained its original shape," Widrig added. This allowed the researchers to scan the animal's breastbone, which is where the muscles that enable flight would have been attached.

They determined that Lithornis promiscuus was able to fly -- either by continuously beating its wings or alternating between flapping and gliding.

But this discovery prompts another question: why did these birds give up the power of flight?

- Taking to the ground -

"Birds tend to evolve flightlessness when two important conditions are met: they have to be able to obtain all their food on the ground, and there cannot be any predators to threaten them," Widrig explained.

Other research has also recently revealed that lithornithids may have had a bony organ on the tip of their beaks which made them excel at foraging for insects.

But what about the second condition -- a lack of predators?

Widrig suspects that palaeognath ancestors likely started evolving towards flightlessness after dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago.

"With all the major predators gone, ground-feeding birds would have been free to become flightless, which would have saved them a lot of energy," she said.

The small mammals that survived the event that wiped out the dinosaurs -- thought to have been a huge asteroid -- would have taken some time to evolve into predators.

This would have given flightless birds "time to adapt by becoming swift runners" like the emu, ostrich and rhea -- or even "becoming themselves dangerous and intimidating, like the cassowary," she said.

The study was published in the Royal Society's Biology Letters journal.

H.Weber--VB