-

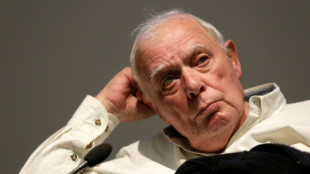

Portugal mourns acclaimed writer Antonio Lobo Antunes

Portugal mourns acclaimed writer Antonio Lobo Antunes

-

Union loses fight against Tesla at German factory

-

Wales revel in being the underdogs, says skipper Lake

Wales revel in being the underdogs, says skipper Lake

-

German school students rally against army recruitment drive

-

Wary European states pledge military aid for Cyprus, Gulf

Wary European states pledge military aid for Cyprus, Gulf

-

Liverpool injuries frustrating Slot in tough season

-

Real Madrid will 'keep fighting' in title race, vows Arbeloa

Real Madrid will 'keep fighting' in title race, vows Arbeloa

-

Australia join South Korea in quarters of Women's Asian Cup

-

Kane to miss Bayern game against Gladbach with calf knock

Kane to miss Bayern game against Gladbach with calf knock

-

Henman says Raducanu needs more physicality to rise up rankings

-

France recall fit-again Jalibert to face Scotland

France recall fit-again Jalibert to face Scotland

-

Harry Styles fans head in one direction: to star's home village

-

Syrian jailed over stabbing at Berlin Holocaust memorial

Syrian jailed over stabbing at Berlin Holocaust memorial

-

Second Iranian ship heading to Sri Lanka after submarine attack

-

Middle East war spirals as Iran hits Kurds in Iraq

Middle East war spirals as Iran hits Kurds in Iraq

-

Norris hungrier than ever to defend Formula One world title

-

Fatherhood, sleep, T20 World Cup final: Henry's whirlwind journey

Fatherhood, sleep, T20 World Cup final: Henry's whirlwind journey

-

Conservative Nigerian city sees women drive rickshaw taxis

-

T20 World Cup hero Allen says New Zealand confidence high for final

T20 World Cup hero Allen says New Zealand confidence high for final

-

The silent struggle of an anti-war woman in Russia

-

Iran hits Kurdish groups in Iraq as conflict widens

Iran hits Kurdish groups in Iraq as conflict widens

-

China sets lowest growth target in decades as consumption lags

-

Afghans rally against Pakistan and civilian casualties

Afghans rally against Pakistan and civilian casualties

-

South Korea beat Philippines 3-0 to reach women's quarter-finals

-

Mercedes' Russell not fazed by being tipped as pre-season favourite

Mercedes' Russell not fazed by being tipped as pre-season favourite

-

Australia beat Taiwan in World Baseball Classic opener

-

Underdogs Wales could hurt Irish after Scotland display: Popham

Underdogs Wales could hurt Irish after Scotland display: Popham

-

Gilgeous-Alexander rules over Knicks again in Thunder win

-

Hamilton reveals sequel in the works to blockbuster 'F1: The Movie'

Hamilton reveals sequel in the works to blockbuster 'F1: The Movie'

-

Alonso, Stroll fear 'permanent nerve damage' from vibrating Aston Martin

-

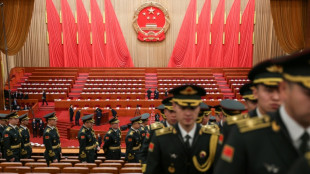

China boosts military spending with eyes on US, Taiwan

China boosts military spending with eyes on US, Taiwan

-

Seoul leads rebound across Asian stocks, oil extends gains

-

Tourism on hold as Middle East war casts uncertainty

Tourism on hold as Middle East war casts uncertainty

-

Bayern and Kane gambling with house money as Gladbach come to town

-

Turkey invests in foreign legion to deliver LA Olympics gold

Turkey invests in foreign legion to deliver LA Olympics gold

-

Galthie's France blessed with unprecedented talent: Saint-Andre

-

Voice coach to the stars says Aussie actors nail tricky accents

Voice coach to the stars says Aussie actors nail tricky accents

-

Rahm rejection of DP World Tour deal 'a shame' - McIlroy

-

Israel keeps up Lebanon strikes as ground forces advance

Israel keeps up Lebanon strikes as ground forces advance

-

China prioritises energy and diplomacy over Iran support

-

Canada PM Carney says can't rule out military participation in Iran war

Canada PM Carney says can't rule out military participation in Iran war

-

Verstappen says new Red Bull car gave him 'goosebumps'

-

Swiss to vote on creating giant 'climate fund'

Swiss to vote on creating giant 'climate fund'

-

Google to open German centre for 'AI development'

-

Winter Paralympics to start with icy blast as Ukraine lead ceremony boycott

Winter Paralympics to start with icy blast as Ukraine lead ceremony boycott

-

Sci-fi without AI: Oscar nominated 'Arco' director prefers human touch

-

Ex-guerrillas battle low support in Colombia election

Ex-guerrillas battle low support in Colombia election

-

'She's coming back': Djokovic predicts Serena return

-

Hamilton vows 'no holding back' in his 20th Formula One season

Hamilton vows 'no holding back' in his 20th Formula One season

-

Two-thirds of Cuba, including Havana, hit by blackout

Al-Qaida’s growing ambitions

In recent years, Al‑Qaida has quietly restructured and expanded key elements of its network — from training camps and regional affiliates in Afghanistan and beyond, to renewed focus on propaganda and recruitment through modern communications. This resurgence, though still fragmented, increasingly suggests that Al-Qaida is laying groundwork not only for sporadic terror attacks, but for establishing durable footholds which could evolve into de facto zones of control — a development that should alarm European security institutions.

Once seen as largely diminished with the removal of high-profile leadership, Al-Qaida has demonstrated remarkable resilience. Its decentralized “network of networks” model enables local affiliates and loosely connected cells to operate with considerable autonomy, while still drawing ideological coherence and logistical support from the core. This model lowers entry barriers for local militant groups inspired by its ideology — a subtle but potent evolution from the classic “top-down” terror organization.

Moreover, Al-Qaida’s adoption of new technologies complicates detection. Terrorist actors increasingly rely on encrypted platforms, the dark web, and even generative-AI tools to recruit, radicalize and coordinate operations. This digital shift enables remote radicalization and planning, reducing the need for physical sanctuaries — but also masking activities from traditional intelligence and law-enforcement scrutiny.

Regions of instability — such as parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and the Sahel — have become fertile ground for Al-Qaida’s expansion. These zones, often neglected in public discourse, now serve as incubators for networks that may aim to export influence, operatives, or refugees toward Europe. Historical experience shows that even small cells — when radicalized, organized, and motivated — can inflict damage beyond their geographical origins.

For Europe, the threat lies not only in headline-grabbing terror attacks, but in the gradual erosion of security through infiltration, radicalization, sleeper-cells, and covert networks. Should Al-Qaida succeed in consolidating territories or safe havens, the challenge would shift from reactive counterterrorism to a strategic struggle over long-term stability.

Now more than ever, European governments and institutions must treat Al-Qaida as a dynamic, evolving network — not a relic of the past. Proactive, coordinated efforts in intelligence-sharing, deradicalization, monitoring of migration flows, and disruption of online propaganda are crucial. Ignoring the signs of Al-Qaida’s silent reorganization would be a dangerous gamble: the consequences could redefine Europe’s security landscape for decades.

Mike Pence: U.S. will continue to support Ukraine

Activists organise "flotilla" with aid for Gaza

Holy souls on display at 2024 Venice Biennale

Brussels, my Love? EU-Market "sexy" for voters?

The great Cause: Biden-Harris 2024

UN: Tackling gender inequality crucial to climate crisis

Scientists: "Mini organs" from human stem cells

ICC demands arrest of Russian officers

Europe and its "big" goals for clean hydrogen

Putin and the murder of Alexei Navalny (47†)

Measles: UK authorities call for vaccinate children