-

Who rules the seas? Torpedoed Iran ship brings focus underwater

Who rules the seas? Torpedoed Iran ship brings focus underwater

-

Mideast war escalates as fresh strikes batter Iran

-

Pirovano takes downhill at Val di Fassa for first World Cup win

Pirovano takes downhill at Val di Fassa for first World Cup win

-

Iran drone strike on Azerbaijan raises fears of Mideast war spreading to Caucasus

-

Decades of planning and US backing helps fuel Israel's air power

Decades of planning and US backing helps fuel Israel's air power

-

Hungary to expel seven Ukrainians as Zelensky, Orban quarrel over Russian oil

-

Mideast war is heightening uncertainty, Lufthansa warns

Mideast war is heightening uncertainty, Lufthansa warns

-

Fresh Israeli strikes on Lebanon as PM warns of 'looming humanitarian disaster'

-

Italian general challenges Meloni from the right

Italian general challenges Meloni from the right

-

China says 'clearly aware' of economic risks, vows to boost spending

-

Hungary detains seven Ukrainians as Kyiv, Budapest quarrel over Russian oil

Hungary detains seven Ukrainians as Kyiv, Budapest quarrel over Russian oil

-

North Korea, China power into Women's Asian Cup quarter-finals

-

Extensive destruction in Beirut's southern suburbs following Israeli strikes

Extensive destruction in Beirut's southern suburbs following Israeli strikes

-

Most Asian equities drop as Mideast crisis rages, though oil dips

-

'Super special' Allen can light up big occasion for New Zealand

'Super special' Allen can light up big occasion for New Zealand

-

'Genie' Bumrah: India's yorker king who carries a billion hopes

-

'There will be nerves': India face New Zealand for T20 World Cup glory

'There will be nerves': India face New Zealand for T20 World Cup glory

-

Lufthansa warns of heightened 'uncertainty' from Mideast war

-

Mideast war enters 'next phase' as strikes hit Iran, Lebanon

Mideast war enters 'next phase' as strikes hit Iran, Lebanon

-

Equities mixed as Mideast crisis rages, though oil dips

-

Sri Lanka denounces war deaths, houses Iran sailors

Sri Lanka denounces war deaths, houses Iran sailors

-

Inoue primed for 'historic' Nakatani clash in Tokyo

-

Italy challenges EU over key climate tool

Italy challenges EU over key climate tool

-

Home hero Piastri edges Antonelli in second Australian GP practice

-

Australia forces porn sites to block under-18s from Monday

Australia forces porn sites to block under-18s from Monday

-

Ukraine accuses Hungary of taking 'hostage' bank staff carrying $40 mn

-

Aston Martin chief Newey says no quick fix to vibration problems

Aston Martin chief Newey says no quick fix to vibration problems

-

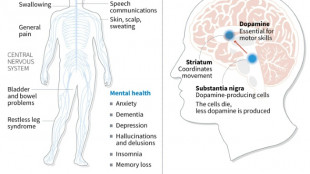

Japan approves stem-cell treatment for Parkinson's in world first

-

Heavy attacks hit Tehran as Israel says war in 'new phase'

Heavy attacks hit Tehran as Israel says war in 'new phase'

-

North Korea thrash Bangladesh in Women's Asian Cup warning

-

Hong Kong mogul Jimmy Lai will not appeal national security conviction: lawyer

Hong Kong mogul Jimmy Lai will not appeal national security conviction: lawyer

-

Eight dead, four missing in Brazil seniors home collapse

-

Paralympics brace for tense opening as Russia comes in from the cold

Paralympics brace for tense opening as Russia comes in from the cold

-

Leclerc edges Hamilton to go fastest in first Australian GP practice

-

Equities mostly drop as Mideast crisis rages, though oil dips

Equities mostly drop as Mideast crisis rages, though oil dips

-

Nepal counts votes after key post-uprising election

-

Italy half-backs can make difference against England: ex-coach Mallett

Italy half-backs can make difference against England: ex-coach Mallett

-

Scotland coach Townsend hails 'instinctive' France ahead of key Six Nations game

-

French starlet Seixas to take on Pogacar at Strade Bianche

French starlet Seixas to take on Pogacar at Strade Bianche

-

Brazil's Petrobras sees profit soar on record output

-

Arsenal, Chelsea aim to avoid FA Cup upsets

Arsenal, Chelsea aim to avoid FA Cup upsets

-

Middle East war enters seventh day as Israel strikes Beirut

-

Qualifier Parry ends Venus's desert dream

Qualifier Parry ends Venus's desert dream

-

Iran missile barrage sparks explosions over Tel Aviv

-

US says Venezuela to protect mining firms as diplomatic ties restored

US says Venezuela to protect mining firms as diplomatic ties restored

-

Trump honors Messi and MLS Cup champion Miami teammates

-

Dismal Spurs can still avoid relegation vows Tudor

Dismal Spurs can still avoid relegation vows Tudor

-

Berger sets early pace at Arnold Palmer with 'unbelievable' 63

-

Morocco part company with coach Regragui as World Cup looms

Morocco part company with coach Regragui as World Cup looms

-

Lens beat Lyon on penalties to reach French Cup semis

Neanderthals, humans co-existed in Europe for over 2,000 years: study

Neanderthals and humans lived alongside each other in France and northern Spain for up to 2,900 years, modelling research suggested Thursday, giving them plenty of time to potentially learn from or even breed with each other.

While the study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, did not provide evidence that humans directly interacted with Neanderthals around 42,000 years ago, previous genetic research has shown that they must have at some point.

Research by Swedish paleogeneticist Svante Paabo, who won the medicine Nobel prize last week, helped reveal that people of European descent -- and almost everyone worldwide -- have a small percentage of Neanderthal DNA.

Igor Djakovic, a PhD student at Leiden University in the Netherlands and lead author of the new study, said we know that humans and Neanderthals "met and integrated in Europe, but we have no idea in which specific regions this actually happened".

Exactly when this happened has also proved elusive, though previous fossil evidence has suggested that modern humans and Neanderthals walked the Earth at the same time for thousands of years.

To find out more, the Leiden-led team looked at radiocarbon dating for 56 artefacts -- 28 each for Neanderthals and humans -- from 17 sites across France and northern Spain.

The artefacts included bones as well as distinctive stone knives thought to have been made by some of the last Neanderthals in the region.

The researchers then used Bayesian modelling to narrow down the potential date ranges.

- 'Never really went extinct' -

Then they used optimal linear estimation, a new modelling technique they adapted from biological conservation sciences, to get the best estimate for when the region's last Neanderthals lived.

Djakovic said the "underlying assumption" of this technique is that we are unlikely to ever discover the first or last members of an extinct species.

"For example, we'll never find the last woolly Rhino," he told AFP, adding that "our understanding is always broken up into fragments".

The modelling found that Neanderthals in the region went extinct between 40,870 and 40,457 years ago, while modern humans first appeared around 42,500 years ago.

This means the two species lived alongside each other in the region for between 1,400 and 2,900 years, the study said.

During this time there are indications of a great "diffusion of ideas" by both humans and Neanderthals, Djakovic said.

The period is "associated with substantial transformations in the way that people are producing material culture," such as tools and ornaments, he said.

There was also a "quite severe" change in the artefacts produced by Neanderthals, which started to look much more like those made by humans, he added.

Given the changes in culture and the evidence in our own genes, the new timeline could further bolster a leading theory for the end of the Neanderthals: mating with humans.

Breeding with the larger human population could have meant that, over time, Neanderthals were "effectively swallowed into our gene pool," Djakovic said.

"When you combine that with what we know now -- that most people living on Earth have Neanderthal DNA -- you could make the argument that they never really went extinct, in a certain sense."

P.Anderson--BTB