-

Man City sign Palace defender Guehi

Man City sign Palace defender Guehi

-

Under-fire Frank claims backing of Spurs hierarchy

-

Prince Harry, Elton John 'violated' by UK media's alleged intrusion

Prince Harry, Elton John 'violated' by UK media's alleged intrusion

-

Syria offensive leaves Turkey's Kurds on edge

-

Man City announce signing of defender Guehi

Man City announce signing of defender Guehi

-

Ivory Coast faces unusual pile-up of cocoa at export hubs

-

Senegal 'unsporting' but better in AFCON final, say Morocco media

Senegal 'unsporting' but better in AFCON final, say Morocco media

-

New charges against son of Norway princess

-

What is Trump's 'Board of Peace'?

What is Trump's 'Board of Peace'?

-

Mbappe calls out Madrid fans after Vinicius jeered

-

Russians agree to sell sanctioned Serbian oil firm

Russians agree to sell sanctioned Serbian oil firm

-

Final chaos against Senegal leaves huge stain on Morocco's AFCON

-

Germany brings back electric car subsidies to boost market

Germany brings back electric car subsidies to boost market

-

Europe wants to 'avoid escalation' on Trump tariff threat: Merz

-

Syrian army deploys in former Kurdish-held areas under ceasefire deal

Syrian army deploys in former Kurdish-held areas under ceasefire deal

-

Louvre closes for the day due to strike

-

Prince Harry lawyer claims 'systematic' UK newspaper group wrongdoing as trial opens

Prince Harry lawyer claims 'systematic' UK newspaper group wrongdoing as trial opens

-

Centurion Djokovic romps to Melbourne win as Swiatek, Gauff move on

-

Brignone unsure about Olympics participation ahead of World Cup comeback

Brignone unsure about Olympics participation ahead of World Cup comeback

-

Roger Allers, co-director of "The Lion King", dead at 76

-

Senegal awaits return of 'heroic' AFCON champions

Senegal awaits return of 'heroic' AFCON champions

-

Trump to charge $1bn for permanent 'peace board' membership: reports

-

Trump says world 'not secure' until US has Greenland

Trump says world 'not secure' until US has Greenland

-

Gold hits peak, stocks sink on new Trump tariff threat

-

Champions League crunch time as pressure piles on Europe's elite

Champions League crunch time as pressure piles on Europe's elite

-

Harry arrives at London court for latest battle against UK newspaper

-

Swiatek survives scare to make Australian Open second round

Swiatek survives scare to make Australian Open second round

-

Over 400 Indonesians 'released' by Cambodian scam networks: ambassador

-

Japan PM calls snap election on Feb 8 to seek stronger mandate

Japan PM calls snap election on Feb 8 to seek stronger mandate

-

Europe readying steps against Trump tariff 'blackmail' on Greenland: Berlin

-

What is the EU's anti-coercion 'bazooka' it could use against US?

What is the EU's anti-coercion 'bazooka' it could use against US?

-

Infantino condemns Senegal for 'unacceptable scenes' in AFCON final

-

Gold, silver hit peaks and stocks sink on new US-EU trade fears

Gold, silver hit peaks and stocks sink on new US-EU trade fears

-

Trailblazer Eala exits Australian Open after 'overwhelming' scenes

-

Warhorse Wawrinka stays alive at farewell Australian Open

Warhorse Wawrinka stays alive at farewell Australian Open

-

Bangladesh face deadline over refusal to play World Cup matches in India

-

High-speed train collision in Spain kills 39, injures dozens

High-speed train collision in Spain kills 39, injures dozens

-

Gold, silver hit peaks and stocks struggle on new US-EU trade fears

-

Auger-Aliassime retires in Melbourne heat with cramp

Auger-Aliassime retires in Melbourne heat with cramp

-

Melbourne home hope De Minaur 'not just making up the numbers'

-

Risking death, Indians mess with the bull at annual festival

Risking death, Indians mess with the bull at annual festival

-

Ghana's mentally ill trapped between prayer and care

-

UK, France mull social media bans for youth as debate rages

UK, France mull social media bans for youth as debate rages

-

Japan PM to call snap election seeking stronger mandate

-

Switzerland's Ruegg sprints to second Tour Down Under title

Switzerland's Ruegg sprints to second Tour Down Under title

-

China's Buddha artisans carve out a living from dying trade

-

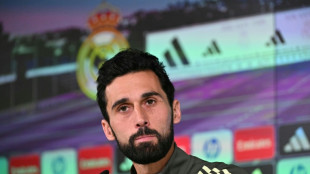

Stroking egos key for Arbeloa as Real Madrid host Monaco

Stroking egos key for Arbeloa as Real Madrid host Monaco

-

'I never felt like a world-class coach', says Jurgen Klopp

-

Ruthless Anisimova races into Australian Open round two

Ruthless Anisimova races into Australian Open round two

-

Australia rest Cummins, Hazlewood, Maxwell for Pakistan T20 series

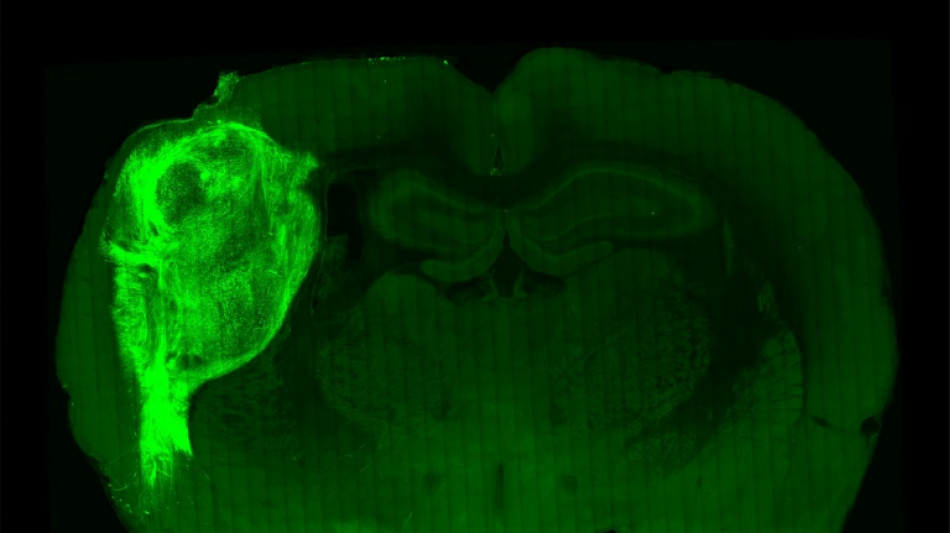

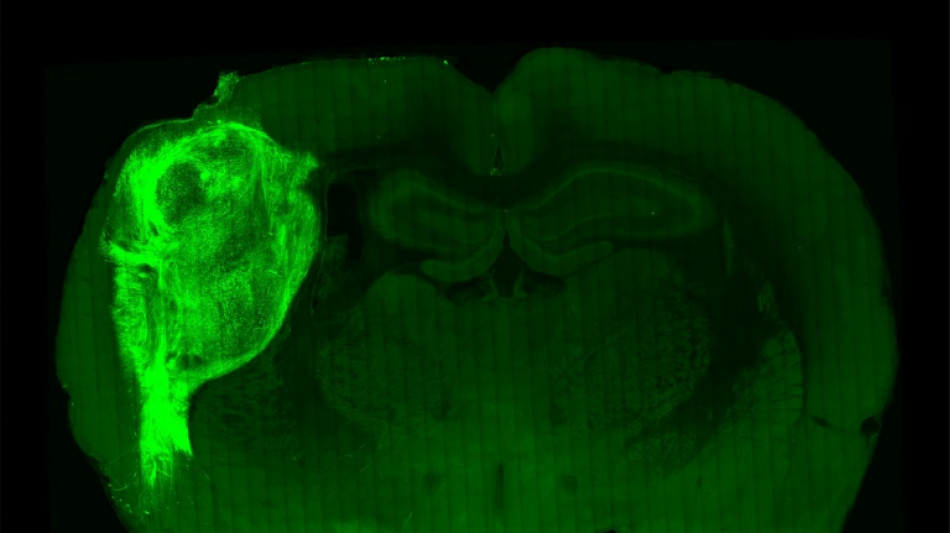

Human brain cells implanted in rats offer research gold mine

Scientists have successfully implanted and integrated human brain cells into newborn rats, creating a new way to study complex psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism, and perhaps eventually test treatments.

Studying how these conditions develop is incredibly difficult -- animals do not experience them like people, and humans cannot simply be opened up for research.

Scientists can assemble small sections of human brain tissue derived from stem cells in petri dishes, and have already done so with more than a dozen brain regions.

But in dishes, "neurons don't grow to the size which a human neuron in an actual human brain would grow", said Sergiu Pasca, the study's lead author and professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences at Stanford University.

And isolated from a body, they cannot tell us what symptoms a defect will cause.

To overcome those limitations, researchers implanted the groupings of human brain cells, called organoids, into the brains of young rats.

The rats' age was important: human neurons have been implanted into adult rats before, but an animal's brain stops developing at a certain age, limiting how well implanted cells can integrate.

"By transplanting them at these early stages, we found that these organoids can grow relatively large, they become vascularised (receive nutrients) by the rat, and they can cover about a third of a rat's (brain) hemisphere," Pasca said.

- Ethical dilemmas -

To test how well the human neurons integrated with the rat brains and bodies, air was puffed across the animals' whiskers, which prompted electrical activity in the human neurons.

That showed an input connection -- external stimulation of the rat's body was processed by the human tissue in the brain.

The scientists then tested the reverse: could the human neurons send signals back to the rat's body?

They implanted human brain cells altered to respond to blue light, and then trained the rats to expect a "reward" of water from a spout when blue light shone on the neurons via a cable in the animals' skulls.

After two weeks, pulsing the blue light sent the rats scrambling to the spout, according to the research published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The team has now used the technique to show that organoids developed from patients with Timothy syndrome grow more slowly and display less electrical activity than those from healthy people.

The technique could eventually be used to test new drugs, according to J. Gray Camp of the Roche Institute for Translational Bioengineering, and Barbara Treutlein of ETH Zurich.

It "takes our ability to study human brain development, evolution and disease into uncharted territory", the pair, who were not involved in the study, wrote in a review commissioned by Nature.

The method raises potentially uncomfortable questions -- how much human brain tissue can be implanted into a rat before the animal's nature is changed? Would the method be ethical in primates?

Pasca argued that limitations on how deeply human neurons integrate with the rat brain provide "natural barriers".

Rat brains develop much faster than human ones, "so there's only so much that the rat cortex can integrate".

But in species closer to humans, those barriers might no longer exist, and Pasca said he would not support using the technique in primates for now.

He argued though that there is a "moral imperative" to find ways to better study and treat psychiatric disorders.

"Certainly the more human these models are becoming, the more uncomfortable we feel," he said.

But "human psychiatric disorders are to a large extent uniquely human. So we're going to have to think very carefully... how far we want to go with some of these models moving forward."

J.Horn--BTB