-

Mertens and Zhang win Australian Open women's doubles title

Mertens and Zhang win Australian Open women's doubles title

-

Venezuelan interim president announces mass amnesty push

-

China factory activity loses steam in January

China factory activity loses steam in January

-

Melania Trump's atypical, divisive doc opens in theatres

-

Bad Bunny set for historic one-two punch at Grammys, Super Bowl

Bad Bunny set for historic one-two punch at Grammys, Super Bowl

-

Five things to watch for on Grammys night Sunday

-

Venezuelan interim president proposes mass amnesty law

Venezuelan interim president proposes mass amnesty law

-

Rose stretches lead at Torrey Pines as Koepka makes cut

-

Online foes Trump, Petro set for White House face-to-face

Online foes Trump, Petro set for White House face-to-face

-

Seattle Seahawks deny plans for post-Super Bowl sale

-

US Senate passes deal expected to shorten shutdown

US Senate passes deal expected to shorten shutdown

-

'Misrepresent reality': AI-altered shooting image surfaces in US Senate

-

Thousands rally in Minneapolis as immigration anger boils

Thousands rally in Minneapolis as immigration anger boils

-

US judge blocks death penalty for alleged health CEO killer Mangione

-

Lens win to reclaim top spot in Ligue 1 from PSG

Lens win to reclaim top spot in Ligue 1 from PSG

-

Gold, silver prices tumble as investors soothed by Trump Fed pick

-

Ko, Woad share lead at LPGA season opener

Ko, Woad share lead at LPGA season opener

-

US Senate votes on funding deal - but shutdown still imminent

-

US charges prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

US charges prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

-

Trump expects Iran to seek deal to avoid US strikes

-

Guterres warns UN risks 'imminent financial collapse'

Guterres warns UN risks 'imminent financial collapse'

-

NASA delays Moon mission over frigid weather

-

First competitors settle into Milan's Olympic village

First competitors settle into Milan's Olympic village

-

Fela Kuti: first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

-

'Schitt's Creek' star Catherine O'Hara dead at 71

'Schitt's Creek' star Catherine O'Hara dead at 71

-

Curran hat-trick seals 11 run DLS win for England over Sri Lanka

-

Cubans queue for fuel as Trump issues energy ultimatum

Cubans queue for fuel as Trump issues energy ultimatum

-

France rescues over 6,000 UK-bound Channel migrants in 2025

-

Surprise appointment Riera named Frankfurt coach

Surprise appointment Riera named Frankfurt coach

-

Maersk to take over Panama Canal port operations from HK firm

-

US arrests prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

US arrests prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

-

Analysts say Kevin Warsh a safe choice for US Fed chair

-

Trump predicts Iran will seek deal to avoid US strikes

Trump predicts Iran will seek deal to avoid US strikes

-

US oil giants say it's early days on potential Venezuela boom

-

Fela Kuti to be first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

Fela Kuti to be first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

-

Trump says Iran wants deal, US 'armada' larger than in Venezuela raid

-

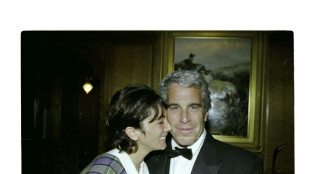

US Justice Dept releases new batch of documents, images, videos from Epstein files

US Justice Dept releases new batch of documents, images, videos from Epstein files

-

Four memorable showdowns between Alcaraz and Djokovic

-

Russian figure skating prodigy Valieva set for comeback -- but not at Olympics

Russian figure skating prodigy Valieva set for comeback -- but not at Olympics

-

Barcelona midfielder Lopez agrees contract extension

-

Djokovic says 'keep writing me off' after beating Sinner in late-nighter

Djokovic says 'keep writing me off' after beating Sinner in late-nighter

-

US Justice Dept releasing new batch of Epstein files

-

South Africa and Israel expel envoys in deepening feud

South Africa and Israel expel envoys in deepening feud

-

French eyewear maker in spotlight after presidential showing

-

Olympic dream 'not over', Vonn says after crash

Olympic dream 'not over', Vonn says after crash

-

Brazil's Lula discharged after cataract surgery

-

US Senate races to limit shutdown fallout as Trump-backed deal stalls

US Senate races to limit shutdown fallout as Trump-backed deal stalls

-

'He probably would've survived': Iran targeting hospitals in crackdown

-

Djokovic stuns Sinner to set up Australian Open final with Alcaraz

Djokovic stuns Sinner to set up Australian Open final with Alcaraz

-

Mateta omitted from Palace squad to face Forest

Good neighbors: Bonobo study offers clues into early human alliances

Human society is founded on our ability to cooperate with others beyond our immediate family and social groups.

And according to a study published Thursday in the journal Science, we're not alone: bonobos team up with outsiders too, in everything from grooming to food sharing, even forming alliances against sexual aggressors.

Lead author Liran Samuni of the German Primate Center in Gottingen told AFP that studying the primates offered a "window into our past," possibly signaling an evolutionary basis for how our own species began wider-scale collaborative endeavors.

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) are our closest living relatives, alongside chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), and the two species are also very closely related to each other.

But while encounters between chimpanzee groups are inherently hostile and often result in lethal violence, interactions between bonobo parties hadn't been as well examined.

That's because bonobos, an endangered species, are notoriously difficult to study in their natural habitat -- and they live only in remote regions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

With research on chimps dominating the literature, some scientists assumed hostility against outsiders was innate to human nature -- something we had perhaps trained ourselves to get past by inventing new social norms, even as that trait lurked deep inside.

- Female coalitions against sexual aggression -

In the new paper, Samuni teamed up with Martin Surbeck, a professor at Harvard who founded the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve, to carry out a long-term study over two years.

"The first thing they do... is try to run away from you," Surbeck told AFP, explaining it took a long time for the bonobos to overcome their inherent fears of humans and behave normally.

Days began at 4:00 am and involved researchers trekking through the dark forest until they reached bonobo nests, then waiting for sunrise so they could follow the apes throughout the day, aided by indigenous Mongandu trackers.

Samuni and Surbeck focused on two small bonobo groups of 11 and 20 adults respectively, and found to their surprise they spent 20 percent of their total time together -- feeding, resting, traveling and more.

"Every individual is different," said Samuni. "There are those that are more introverts, extroverts, there are those that are more pro-social than others."

The team found that cooperation between the groups was driven largely by a select few who were more helpful within their own group. These individuals tended to connect with similar "pro-social" bonobos from the other group, creating a system of mutual benefit, or "reciprocal altruism."

The positive interactions occurred despite a low level of genetic relatedness between the groups, and despite the fact that reciprocity -- such as paying back a gift of fruit -- often took place much later, in future encounters.

Intriguingly, females, both within and from different groups, were found to form coalitions -- sometimes to chase an individual from a feeding tree, at other times to prevent a coercive sexual advance from a male.

"We don't see sexual coercion in bonobos, which is a common phenomenon in chimpanzees," said Surbeck. "One aspect of that might be due to those female coalitions, that help the females to maintain reproductive autonomy."

- Are we more like chimps or bonobos? -

The authors suggest their research offers an "alternative scenario" to the idea human cooperation is against our nature, or that we broadened cooperation with outsiders by first merging our extended families.

But "this does not mean that reconstructions of ancestral hominin species should be based only on bonobos," Joan Silk, a scientist at Arizona State University wrote in a related commentary.

There are other ways in which chimpanzees seem closer to humans than bonobos -- for example they more often hunt animal prey and use tools. Male chimpanzees also form strong bonds with fellow males and support them in aggressive acts, while bonobo males form stronger ties to females.

Understanding the natural selection forces that created these differences "may help to elucidate how and why humans became such an unusual ape," she concluded.

A.Ammann--VB