-

US border chief says not 'surrendering' immigration mission

US border chief says not 'surrendering' immigration mission

-

EU to put Iran Guards on 'terrorist list'

-

Pegula calls herself 'shoddy, erratic' in Melbourne semi-final loss

Pegula calls herself 'shoddy, erratic' in Melbourne semi-final loss

-

All hands on deck: British Navy sobers up alcohol policy

-

Sabalenka says Serena return would be 'cool' after great refuses to rule it out

Sabalenka says Serena return would be 'cool' after great refuses to rule it out

-

Rybakina plots revenge over Sabalenka in Australian Open final

-

Irish Six Nations hopes hit by Aki ban

Irish Six Nations hopes hit by Aki ban

-

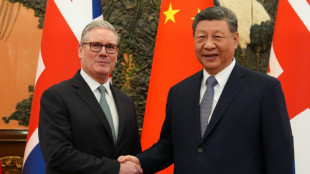

Britain's Starmer hails 'good progress' after meeting China's Xi

-

Parrots rescued as landslide-hit Sicilian town saves pets

Parrots rescued as landslide-hit Sicilian town saves pets

-

Gold surges further, oil jumps on Trump's Iran threat

-

No handshake as Sabalenka sets up repeat of 2023 Melbourne final

No handshake as Sabalenka sets up repeat of 2023 Melbourne final

-

Iran's IRGC: the feared 'Pasdaran' set for EU terror listing

-

EU eyes migration clampdown with push on deportations, visas

EU eyes migration clampdown with push on deportations, visas

-

Umpire call fired up Sabalenka in politically charged Melbourne clash

-

Rybakina battles into Australian Open final against Sabalenka

Rybakina battles into Australian Open final against Sabalenka

-

Iran vows 'crushing response', EU targets Revolutionary Guards

-

Northern Mozambique: massive gas potential in an insurgency zone

Northern Mozambique: massive gas potential in an insurgency zone

-

Gold demand hits record high on Trump policy doubts: industry

-

Show must go on: London opera chief steps in for ailing tenor

Show must go on: London opera chief steps in for ailing tenor

-

UK drugs giant AstraZeneca announces $15 bn investment in China

-

US scrutiny of visitors' social media could hammer tourism: trade group

US scrutiny of visitors' social media could hammer tourism: trade group

-

'Watch the holes'! Paris fashion crowd gets to know building sites

-

Power, pace and financial muscle: How Premier League sides are ruling Europe

Power, pace and financial muscle: How Premier League sides are ruling Europe

-

'Pesticide cocktails' pollute apples across Europe: study

-

Ukraine's Svitolina feels 'very lucky' despite Australian Open loss

Ukraine's Svitolina feels 'very lucky' despite Australian Open loss

-

Money laundering probe overshadows Deutsche Bank's record profits

-

Huge Mozambique gas project restarts after five-year pause

Huge Mozambique gas project restarts after five-year pause

-

Britain's Starmer reports 'good progress' after meeting China's Xi

-

Sabalenka crushes Svitolina in politically charged Australian Open semi

Sabalenka crushes Svitolina in politically charged Australian Open semi

-

Turkey to offer mediation on US–Iran tensions, weighs border measures

-

Mali's troubled tourism sector crosses fingers for comeback

Mali's troubled tourism sector crosses fingers for comeback

-

China issues 73 life bans, punishes top football clubs for match-fixing

-

Ghana moves to rewrite mining laws for bigger share of gold revenues

Ghana moves to rewrite mining laws for bigger share of gold revenues

-

South Africa drops 'Melania' just ahead of release

-

Senegal coach Thiaw banned, fined after AFCON final chaos

Senegal coach Thiaw banned, fined after AFCON final chaos

-

Russia's sanctioned oil firm Lukoil to sell foreign assets to Carlyle

-

Australian Open chief Tiley says 'fine line' after privacy complaints

Australian Open chief Tiley says 'fine line' after privacy complaints

-

Trump-era trade stress leads Western powers to China

-

Gold soars towards $5,600 as Trump rattles sabre over Iran

Gold soars towards $5,600 as Trump rattles sabre over Iran

-

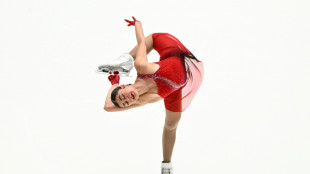

Russia's Petrosian skates in Valieva shadow at Milan-Cortina Olympics

-

China executes 11 linked to Myanmar scam compounds

China executes 11 linked to Myanmar scam compounds

-

Germany to harden critical infrastructure as Russia fears spike

-

Colombia plane crash investigators battle poor weather to reach site

Colombia plane crash investigators battle poor weather to reach site

-

Serena Williams refuses to rule out return to tennis

-

Vietnam, EU vow stronger ties as bloc's chief visits Hanoi

Vietnam, EU vow stronger ties as bloc's chief visits Hanoi

-

New glove, same fist: Myanmar vote ensures military's grip

-

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

Deutsche Bank logs record profits, as new probe casts shadow

-

Thai foreign minister says hopes Myanmar polls 'start of transition' to peace

-

No white flag from Djokovic against Sinner as Alcaraz faces Zverev threat

No white flag from Djokovic against Sinner as Alcaraz faces Zverev threat

-

Vietnam and EU upgrade ties as EU chief visits Hanoi

Ozone-depleting CFCs hit record despite ban: study

Their power to dissolve the ozone layer shielding Earth from the Sun prompted a worldwide ban, but scientists on Monday revealed that some human-made chlorofluorocarbons have reached record levels, boosting climate-changing emissions.

Despite being banned under the Montreal Protocol, the five chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) measured increased rapidly in the atmosphere from 2010 to 2020, reaching record-high levels in 2020, according to the study published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

It said the increase was probably due to leakage during the production of chemicals that are meant to replace CFCs, including hydrofluorocarbons (HFOs).

Although at current levels they do not threaten the recovery of the ozone layer, they contribute to a different threat, joining other emissions in heating the atmosphere.

"If you are producing greenhouse gases and ozone-depleting substances during the production of these next-generation compounds, then they do have an indirect impact on the climate and the ozone layer," said co-author Isaac Vimont of the Global Monitoring Laboratory at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

CFCs are potent greenhouse gases that trap heat up to 10,000 times more efficiently than carbon dioxide -- the biggest cause of the global warming that drives climate change, according to data from the Global Carbon Project.

In the 1970s and 1980s, CFCs were widely used as refrigerants and in aerosol sprays.

But the discovery of the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica as a result of their use led to the global agreement in 1987 to eliminate them.

After the Montreal Protocol entered into force, global concentrations of CFCs declined steadily.

- Ozone 'early warning' -

The study analysed five CFCs with no or few current uses, beginning at the point of their total global phase-out in 2010.

In 2020 all five gases were at their highest abundance since direct measurements began.

Those emissions have so far resulted in a modest impact on the ozone layer and slightly larger climate footprint, said co-author Luke Western of Bristol University and the Global Monitoring Laboratory.

They are equivalent to the 2020 CO2 emissions of Switzerland -- about one percent of the total greenhouse gas emissions of the United States.

But if the rapid upward trend continues, their impact will increase.

The researchers called their findings "an early warning" of a new way in which CFCs are endangering the ozone layer.

The emissions are likely due to processes that are not subject to the current ban and unreported uses.

The class of industrial aerosols developed to replace those banned by the Montreal Protocol is to be phased out over the next three decades under a recent amendment to the 1987 treaty.

- Unknown source -

The protocol curbs the release of ozone-depleting substances that could disperse, but does not ban their use in the production of other chemicals as raw materials or by-products.

It was not the first time that unreported production had an impact on CFC levels. In 2018 scientists discovered that the pace of CFC slowdown had dropped by half from the preceding five years.

Evidence in that case pointed to factories in eastern China, the researchers said. Once CFC production in that region stopped, the draw-down appeared to be back on track.

The study said further research was needed to know the precise source of the recent rise in CFC emissions.

Nationwide data gaps make it difficult to determine where the gases are coming from and for some of the CFCs analysed there are no known uses.

But "eradicating these emissions is an easy win in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions," said Western.

K.Thomson--BTB