-

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

'Extraordinary' trove of ancient species found in China quarry

-

Villa's Tielemans ruled out for up to 10 weeks

-

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

Google unveils AI tool probing mysteries of human genome

-

UK proposes to let websites refuse Google AI search

-

'I wanted to die': survivors recount Mozambique flood terror

'I wanted to die': survivors recount Mozambique flood terror

-

Trump issues fierce warning to Minneapolis mayor over immigration

-

Anglican church's first female leader confirmed at London service

Anglican church's first female leader confirmed at London service

-

Germany cuts growth forecast as recovery slower than hoped

-

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

Amazon to cut 16,000 jobs worldwide

-

One dead, five injured in clashes between Colombia football fans

-

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

Dollar halts descent, gold keeps climbing before Fed update

-

US YouTuber IShowSpeed gains Ghanaian nationality at end of Africa tour

-

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

Sweden plans to ban mobile phones in schools

-

Turkey football club faces probe over braids clip backing Syrian Kurds

-

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

Deutsche Bank offices searched in money laundering probe

-

US embassy angers Danish veterans by removing flags

-

Netherlands 'insufficiently' protects Caribbean island from climate change: court

Netherlands 'insufficiently' protects Caribbean island from climate change: court

-

Fury confirms April comeback fight against Makhmudov

-

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

Susan Sarandon to be honoured at Spain's top film awards

-

Trump says 'time running out' as Iran rejects talks amid 'threats'

-

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

Spain eyes full service on train tragedy line in 10 days

-

Greenland dispute 'strategic wake-up call for all of Europe,' says Macron

-

'Intimidation and coercion': Iran pressuring families of killed protesters

'Intimidation and coercion': Iran pressuring families of killed protesters

-

Europe urged to 'step up' on defence as Trump upends ties

-

Sinner hails 'inspiration' Djokovic ahead of Australian Open blockbuster

Sinner hails 'inspiration' Djokovic ahead of Australian Open blockbuster

-

Dollar rebounds while gold climbs again before Fed update

-

Aki a doubt for Ireland's Six Nations opener over disciplinary issue

Aki a doubt for Ireland's Six Nations opener over disciplinary issue

-

West Ham sign Fulham winger Traore

-

Relentless Sinner sets up Australian Open blockbuster with Djokovic

Relentless Sinner sets up Australian Open blockbuster with Djokovic

-

Israel prepares to bury last Gaza hostage

-

Iran rejects talks with US amid military 'threats'

Iran rejects talks with US amid military 'threats'

-

Heart attack ends iconic French prop Atonio's career

-

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

SKorean chip giant SK hynix posts record operating profit for 2025

-

Greenland's elite dogsled unit patrols desolate, icy Arctic

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, cuts jobs

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, cuts jobs

-

Musetti rues 'really painful' retirement after schooling Djokovic

-

Russian volcano puts on display in latest eruption

Russian volcano puts on display in latest eruption

-

Thailand uses contraceptive vaccine to limit wild elephant births

-

Djokovic gets lucky to join Pegula, Rybakina in Melbourne semi-finals

Djokovic gets lucky to join Pegula, Rybakina in Melbourne semi-finals

-

Trump says to 'de-escalate' Minneapolis, as aide questions agents' 'protocol'

-

'Extremely lucky' Djokovic into Melbourne semi-finals as Musetti retires

'Extremely lucky' Djokovic into Melbourne semi-finals as Musetti retires

-

'Animals in a zoo': Players back Gauff call for more privacy

-

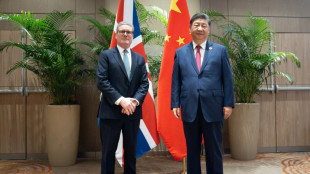

Starmer heads to China to defend 'pragmatic' partnership

Starmer heads to China to defend 'pragmatic' partnership

-

Uganda's Quidditch players with global dreams

-

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

'Hard to survive': Kyiv's elderly shiver after Russian attacks on power and heat

-

South Korea's ex-first lady jailed for 20 months for taking bribes

-

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

Polish migrants return home to a changed country

-

Dutch tech giant ASML posts bumper profits, eyes bright AI future

-

South Korea's ex-first lady jailed for 20 months for corruption

South Korea's ex-first lady jailed for 20 months for corruption

-

Minnesota congresswoman unbowed after attacked with liquid

Sound of Mughal-era sarangi instrument fading away in Pakistan

In the shadow of Lahore's centuries-old Badshahi Mosque, Zohaib Hassan plucks at the strings of a sarangi, filling the streets with a melodious hum and cry.

Remarkable for its resemblance to the human voice, the classical instrument is fading from Pakistan's music scene –- except for a few players dedicated to preserving its place.

Difficult to master, expensive to repair, and with little financial reward for professionals, the sarangi's decline has been difficult to halt, Hassan told AFP.

"We are trying to keep the instrument alive, not even taking into account our miserable financial condition," he said.

For seven generations, his family has mastered the bowed, short-necked instrument and Hassan is well-respected across Pakistan for his abilities, regularly appearing on television, radio and at private parties.

"My family's craze for the instrument forced me to pursue a career as a sarangi player, leaving my education incomplete," he said.

"I live hand-to-mouth as the majority of directors arrange musical programmes with the latest orchestras and pop bands."

Traditional instruments are competing with a booming R&B and pop scene in a country where more than 60 percent of the population is aged under 30.

Sara Zaman, a classical music teacher at the National Council of Arts in Lahore, said alongside the sarangi, other traditional instruments such as the sitar, santoor, and tanpura are also dying out.

"Platforms have been given to other disciplines like pop music, but it has been missing in the case of classical music," she said.

"The sarangi, being a very difficult instrument, has not been given due importance and attention in Pakistan leading to its gradual demise."

- 'The strings of my heart' -

The sarangi gained prominence in Indian classical music in the 17th century, during the reign of the Mughals in the subcontinent.

Its decline began in the 1980s after the death of several master players and classical singers in the country, said Khwaja Najam-ul-Hassan, a television director who has created an archive of Pakistan's leading musicians.

"The instrument was close to the hearts of the top internationally acclaimed male and female classical singers, but it began to fade away after they died," he said.

Ustad Allah Rakha, one of Pakistan's most globally acclaimed sarangi players, died in 2015 after a career that saw him perform with orchestras around the world.

Now players say they struggle to survive on performance fees alone, often much smaller than those paid to modern guitarists, pianists or violinists.

Carved by hand from a single block of cedar native to parts of Pakistan, the sarangi's primary strings are made of goat gut while the seventeen sympathetic strings –- a common feature on subcontinent folk instruments –- are steel.

The instrument costs around 120,000 rupees ($625) and most of its parts are imported from neighbouring India, where it remains a principal part of the canon.

"The price has gone up as there is a ban on imports from India," said Muhammad Tahir, the owner of one of only two repair shops in Lahore.

Pakistan downgraded diplomatic ties and stopped bilateral trade with India over New Delhi's decision in 2019 to strip the disputed Jammu and Kashmir region of its semi-autonomous status.

Tahir, who spends around two months carefully restoring a single worn-out sarangi, said no one in Pakistan manufactures the special steel strings because of the lack of demand.

"There is no admiration for sarangi players and the few people who are repairing this wonderful instrument," said Ustad Zia-ud-Din, the owner of the other Lahore repair shop, which has existed in some form for 200 years.

Efforts to adapt to the modern music scene have shown pockets of promise.

"We have invented new ways of playing, including making the sarangi semi-electric to enhance the sound during performances with modern musical instruments," said Hassan of the academy he runs in Lahore.

He has now performed several times with the adapted instrument, and says the reception has been positive.

One of the few students is 14-year-old musician Mohsin Muddasir, who has shunned instruments such as the guitar to take on the sarangi.

"I am learning this instrument because it plays with the strings of my heart," he said.

J.Fankhauser--BTB