-

Epstein offered ex-prince Andrew meeting with Russian woman: files

Epstein offered ex-prince Andrew meeting with Russian woman: files

-

Jokic scores 31 to propel Nuggets over Clippers in injury return

-

Montreal studio rises from dark basement office to 'Stranger Things'

Montreal studio rises from dark basement office to 'Stranger Things'

-

US government shuts down but quick resolution expected

-

Mertens and Zhang win Australian Open women's doubles title

Mertens and Zhang win Australian Open women's doubles title

-

Venezuelan interim president announces mass amnesty push

-

China factory activity loses steam in January

China factory activity loses steam in January

-

Melania Trump's atypical, divisive doc opens in theatres

-

Bad Bunny set for historic one-two punch at Grammys, Super Bowl

Bad Bunny set for historic one-two punch at Grammys, Super Bowl

-

Five things to watch for on Grammys night Sunday

-

Venezuelan interim president proposes mass amnesty law

Venezuelan interim president proposes mass amnesty law

-

Rose stretches lead at Torrey Pines as Koepka makes cut

-

Online foes Trump, Petro set for White House face-to-face

Online foes Trump, Petro set for White House face-to-face

-

Seattle Seahawks deny plans for post-Super Bowl sale

-

US Senate passes deal expected to shorten shutdown

US Senate passes deal expected to shorten shutdown

-

'Misrepresent reality': AI-altered shooting image surfaces in US Senate

-

Thousands rally in Minneapolis as immigration anger boils

Thousands rally in Minneapolis as immigration anger boils

-

US judge blocks death penalty for alleged health CEO killer Mangione

-

Lens win to reclaim top spot in Ligue 1 from PSG

Lens win to reclaim top spot in Ligue 1 from PSG

-

Gold, silver prices tumble as investors soothed by Trump Fed pick

-

Ko, Woad share lead at LPGA season opener

Ko, Woad share lead at LPGA season opener

-

US Senate votes on funding deal - but shutdown still imminent

-

US charges prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

US charges prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

-

Trump expects Iran to seek deal to avoid US strikes

-

Guterres warns UN risks 'imminent financial collapse'

Guterres warns UN risks 'imminent financial collapse'

-

NASA delays Moon mission over frigid weather

-

First competitors settle into Milan's Olympic village

First competitors settle into Milan's Olympic village

-

Fela Kuti: first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

-

'Schitt's Creek' star Catherine O'Hara dead at 71

'Schitt's Creek' star Catherine O'Hara dead at 71

-

Curran hat-trick seals 11 run DLS win for England over Sri Lanka

-

Cubans queue for fuel as Trump issues energy ultimatum

Cubans queue for fuel as Trump issues energy ultimatum

-

France rescues over 6,000 UK-bound Channel migrants in 2025

-

Surprise appointment Riera named Frankfurt coach

Surprise appointment Riera named Frankfurt coach

-

Maersk to take over Panama Canal port operations from HK firm

-

US arrests prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

US arrests prominent journalist after Minneapolis protest coverage

-

Analysts say Kevin Warsh a safe choice for US Fed chair

-

Trump predicts Iran will seek deal to avoid US strikes

Trump predicts Iran will seek deal to avoid US strikes

-

US oil giants say it's early days on potential Venezuela boom

-

Fela Kuti to be first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

Fela Kuti to be first African to get Grammys Lifetime Achievement Award

-

Trump says Iran wants deal, US 'armada' larger than in Venezuela raid

-

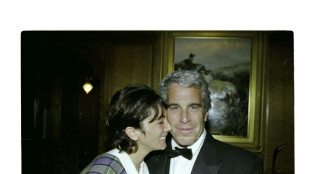

US Justice Dept releases new batch of documents, images, videos from Epstein files

US Justice Dept releases new batch of documents, images, videos from Epstein files

-

Four memorable showdowns between Alcaraz and Djokovic

-

Russian figure skating prodigy Valieva set for comeback -- but not at Olympics

Russian figure skating prodigy Valieva set for comeback -- but not at Olympics

-

Barcelona midfielder Lopez agrees contract extension

-

Djokovic says 'keep writing me off' after beating Sinner in late-nighter

Djokovic says 'keep writing me off' after beating Sinner in late-nighter

-

US Justice Dept releasing new batch of Epstein files

-

South Africa and Israel expel envoys in deepening feud

South Africa and Israel expel envoys in deepening feud

-

French eyewear maker in spotlight after presidential showing

-

Olympic dream 'not over', Vonn says after crash

Olympic dream 'not over', Vonn says after crash

-

Brazil's Lula discharged after cataract surgery

Canadian Prairies farmers try to adapt to a warming world

Following repeated droughts, Canadian farmers are trying to adapt to a new era in agriculture marked by a warming world -- including by trapping snow in their fields, planting heat-resistant crops and seeding earlier in the season.

But it's unclear, they are the first to admit, if their slogging will bear fruit.

Squatting in the middle of a canola field in Alberta, on the western edge of Canada's vast Prairies region, Ian Chitwood surveys the shoots sprouting between long furrows of black soil.

His battle with the heat has been starting earlier every year.

By planting his crops earlier in the season, in May, Chitwood aims to "move up the flowering window," during which the plants are most vulnerable, in order to protect them from the heat in June.

But what his crops really need in the wake of a devastating drought in 2021, he acknowledges, is mild weather and humid soil.

That drought was a "once in 100 years event," says Curtis Rempel of the Canola Council of Canada.

That year, the west of the country sweltered under record high summer temperatures, with the mercury reaching 49.6 degrees Celsius (121.3 Fahrenheit).

"It sure had an impact on yields," reducing them by 50 percent, according to Rempel.

Such hits have had significant impacts on international markets, as Canada exports 90 percent of its canola harvest -- used mostly for cooking oil and biodiesel fuel.

- Water management -

Most canola crops are grown without requiring irrigation in the Prairies, the nation's agricultural heartland spanning nearly 1.8 million square kilometers (695,000 square miles). But the region is sensitive to droughts, whose frequency and severity have been steadily increasing.

In this region, explains Phillip Harder, a hydrology researcher at the University of Saskatchewan, in Saskatoon, "crop production relies on water that accumulates throughout the year." In other words, snow that accumulates over winter and soaks into the ground during the spring thaw.

But howling winds over fields that stretch as far as the eye can see have been blowing away much of that snow of late.

Some farmers have turned to a century-old solution of planting trees in and around their fields to trap the snow.

"In the wintertime when the snow blows it catches in the trees, and then it slowly soaks into the ground," explains Stuart Dougan, a 69-year-old farmer with a weather-beaten face.

In the spring and summer, the trees provide further shelter from the wind "so it's not taking the moisture from the crops," he adds.

Trees may pose new challenges, however, as modern agricultural equipment is much bulkier than in the 1930s when one could more easily plow around a tree trunk, points out Harder.

Alternatively, he recommends when harvesting crops to cut the plants higher on the stem, leaving longer "stubble" sticking out of the ground to "increase snow retention."

- Turning to science -

"We've always looked to keep as much stubble in place to catch the snow and reduce evaporation rates," says Saskatchewan farmer Rob Stone. He, like many Canadian farmers, stopped plowing his fields in the 1990s for this very purpose.

He's now experimenting with new genetically modified seeds that he says hold hope for the future of canola. Four small flags in the middle of his fields mark a test crop.

"As we find ones that are more tolerant (to heat), we will crossbreed them to make a new (plant) population," explains Greg Gingera, a genetics researcher.

Also in the works, adds Rempel, are several companies looking to develop "biologicals or bacteria or fungi that you add to the soil or spray on top of the plant to confer stress tolerance."

But it will be seven to eight years before a product is likely ready to be commercialized and widely available, he says.

In the meantime, farmers will have to make do.

C.Meier--BTB